We cannot live in a world that is not our own, in a world that is interpreted for us by others. An interpreted world is not a home. – Hildegard of Bingen

[Women Part 6 of 9: 1) Introduction, 2) Bodies, 3) Health, 4) Work, 5) Superwomen, 6) Religion, 7) In Tech, 8) Online 9) Conclusions]

I grew up in the Church of England and went to church every Sunday, often twice when I was a chorister: Sung Eucharist in the morning and back for Evensong later on that day. I have always loved high-church ritual: incense, candles, and drama, especially on Good Friday, when the vicar would prostrate himself in front of the altar.

Like many teenage girls with a religious mindset, I wanted to feel a divine transcendence, and watched The Song of Bernadette many times. My brother called it my happy-clappy phase. A Muslim friend of mine said that when she was growing up it was commonly known as la phase mystique for which I was very grateful, as it was a mysterious longing and not happy-clappy at all. And recently I read White Hot Truth, and was like wow, yes, when Danielle La Porte said she too, was desperate, as a religious Roman Catholic, to experience God.

Meggan Watterson, in Reveal, says that before the 9th century, a theologian was someone who had direct experience of the Divine. Nowadays we think of theologians studying and interpreting religion in a cerebral manner. There has long been the idea that we need to transcend our embodiment, which results in organised religion assigning sexuality to the female body (materia – or matter, blood and procreation), and the higher attributes of soul and spirit to the male mind. Watterson, herself a theologian, goes on to say:

And this has always been the reason why, from the Talmud to the New Testament and the Koran, women have been asked to remain silent, […]why their experience is not considered of equal value to that of men.

We are second-class citizens and not worth bothering about. Consequently, it was a Father God who sent his son Jesus to save all mankind, the brotherhood of man, whereas Eve, the first woman in the Bible, is responsible for the downfall of all mankind. She is the temptress with the forbidden fruit and her pal the snake aka the devil incarnate.

In her book The Dance of the Dissident Daughter, Sue Monk Kidd says that prior to Christianity the snake was a symbol of feminine power, wisdom and regeneration, adding that no wonder a woman will feel lost in organised religion as she is cut off from her intuition, which is an evil thing, and which she understands from listening to her body, which is a dirty thing tempting men into sinning.

Both Watterson and Monk Kidd discuss the irony of the Eucharist. This is body which is given for you… this is my blood which is shed for you. Women can give their bodies to breastfeed their kids, and they shed blood every month so that they are able to create new life, but in religious terms, this earthly way is unclean and unspiritual, which is why women were not, until fairly recently, allowed to handle the Eucharist or play a role in the service.

But then religion is a man-made power structure. We had the Holy Roman Empire, which wasn’t about God, or experiencing the divine, it was about man and power. And, the Church of England was created by randy King Henry VIII who wanted to divorce Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry and have sex with Anne Boleyn, whom he then beheaded and called a witch. No divinity there then. As a woman in this faith, I was taught, from birth, to be validated by the masculine, with a male saviour, male vicars, male apostles, and male stories.

It is so indoctrinated in me that until my girls took me to one side at St Paul’s Cathedral after attending a service, and asked me to point out the female apostles and the female saviour, I no longer noticed.

And, therein lies a particularly painful irony, I took my girls to church, because I wanted them to know how to pray in order to find comfort. I wanted for them, in those worst moments which life can serve up, to know their way around a church in case they needed to transcend their earthly troubles and experience the divine. What on earth was I thinking?

A few years ago, after several traumatic life events, I took to weeping a lot in church. Just weeping. I would weep all the way through the service, as it was the only time I had to myself as my girls were in Sunday School being looked after, and I had a tiny slither of time in which I couldn’t do anything but weep.

One day the vicar came over and said:

I have noticed you have been weeping a lot during the service.

And I said:

Yes I am very sad.

And he said:

Don’t you think you should get some help for that? See a counsellor? A therapist? Go see someone.

Basically he didn’t want me in his church as a weeping woman in pain from my life experiences. He wanted me to stop it, to go away, to be silent. I was so upset that he didn’t want me there expressing myself, I told everyone, every woman I came across: female friends, random women in the street, anyone who looked at me. And all the women I talked to said that they too had wept in church and wasn’t that the point of church, to get comfort?

It has taken a while, but I am finally at the opinion that the Church is the last place a woman should look for comfort. Comfort comes from being free from constraint, being at ease, and from the familiar. In contrast, the Bible is full of constraints. All those Thou Shalt Nots… written in a time when women were classed as possessions, not people, don’t put anyone at ease. And, the subjugation of women means that there is no familiar femininity just a load of blokes standing about in dresses, saying things like: This is my body which I give to you. It is mind-boggling that the centre piece of Christianity is something women can do and are considered unclean when they do it, and men cannot do and have turned into a spiritual but cerebral act. Women are to be seen not heard. Do your crying elsewhere, woman.

I did try to stay in the Church. I asked the vicar and a few other ministers if they had anything for me to read on the feminine divine as the whole Jesus thing was no longer working for me. They looked at me like I was insane and made me feel wrong about who I am and how I feel. The results of my life have been experienced in, and written on, my body, a thing that I am supposed to deny, because it is not a divine thing.

Feminist theologian Nicola Slee captures the female role in religion perfectly in Seeking the Risen Christa, when she describes her first experiences of faith in the Methodist Church as an intensely personal quasi-erotic relationship with Jesus [..] which mirrored a white middle-class patriarchal upbringing. He was a trial run for that ultimate act of female self-fulfillment, oh yes the wedding day. Because of course what more does a woman need out of life? And, if this sounds far fetched, look at the Roman Catholic nuns who wore wedding rings because they were the brides of Christ (which always reminded me of the Bride of Frankenstein, who was created like Eve was for Adam, so that Frankenstein could have a bit of company and his laundry done and his tea made). The church is a power structure which reflects an old fashioned outdated patriarchal society in which women are not to be themselves.

And so when this is all the Church has to offer women, what are we to do? Watterson says we have to do what our heart desires and that we are worthy of love and recognition simply because we exist. Something the Church could never say because it wants everyone down on their knees kept inline. They don’t want people following their heart’s desires.

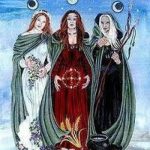

Both Watterson and Monk Kidd have left organised religion to form their own definition of the feminine divine, because she, Herself, can be found, if you know where to look. It is a lot of work, but seems to me to be the only way forward because, as Lucy H Pearce says in The Burning Woman: Feminine stands for all that we have been taught to reject as deeply flawed or inconsequential: our mothers, ourselves, other women, nature – in society, in religion, in work. And this is so wrong.

It’s time to reclaim the feminine, and indeed the feminine divine. It is time to teach our girls that they are whole, and worthy and loved, and that there is nothing wrong with them. It is time to stop making us women wrong about who we are and telling us that the message came from a weirdy-beardy bloke called God.

It is time to reinterpret the message and make it right.

[7) In Tech]

7 comments