If you torture the data enough, it will confess to anything.

– Darrell Huff, How to Lie With Statistics (1954).

[ 1) Introduction, 2) Dialogue or Conversation, 3) User or Used, 4) Codependency or Collaboration, 5) Productive or Experiential, 6) Conclusions]

[update 20/8/20: My guide to human-computer interaction is now available over on Udemy.]

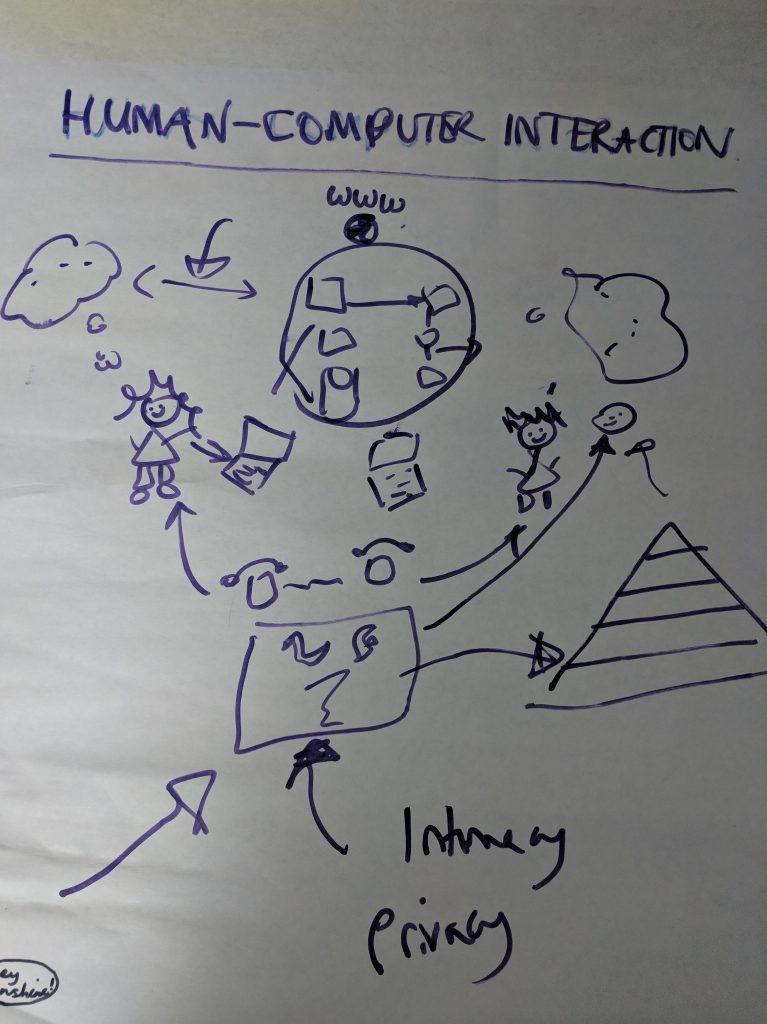

In the last blog I wrote about human dialogue with a computer versus the conversation between humans via a computer. The dialogue with a computer is heavily designed whereas human conversation especially via social media has come about serendipitously. For example, Twitter came from texting which was invented by engineers as tool to test mobile phones.

This is an example of what I call serendipitous design which works by users employing systems to do what they want it to do, which is the no-function-in-structure principle and then a designer find ways to support them. In contrast, the way to create systems which support users to do their job better uses the cardinal rule: know your user with all the various tools and techniques UX designers have borrowed from anthropology. You design with your user in mind, you manage their expectations, and you have them at the front of your mind as a major factor of the design so that the system has specific goals.

But, however hard you try, with each new system or software or form of communication, you often end up changing how people work and the dialogue is less about a field of possibilities with insight, intuition, and creativity, and more about getting people to do extra stuff on top of what they already do. And, because people are keen to get in on whatever new thing is happening they buy into what I call the myth of progress and adopt new ways of working.

This begs the question are we creating systems for users or the used? Today, I was chatting to a roadsweeper, he told me that last year he was driving a lorry but the council’s initiative to reduce carbon emissions means that 80 lorries were taken off the road and the drivers are now out sweeping the streets on foot. He showed me his council-issue mobile phone which tracks his every move and presumably reports back to the office his whereabouts at all times. Not that he needs it, if he sits on a wall too long, local residents will phone the council to complain that he is sitting down and not working hard enough.

Tracking is not new, smart badges, invented at Xerox PARC, were trialled in the 1990s in the early days of ubiquitious computing (ubicomp). The idea was to move computers off the desktop and embed them into our infrastructure so that we interact with them without our knowledge, freeing the user from the need to learn complex systems. In the badges’ case, everyone could be located by everyone else in the building, rather like the Harry Potter Marauder’s map. However, it smacks rather too much of surveillance, especially if your boss decides you are spending too long in the toilet or by the water cooler and, that your behaviour needs to change. The road sweeper instead of a badge has a mobile phone and people who spy on him and grass him up in part because they lack context and don’t know that he is entitled to a 20 minute break.

But it’s not just as part of a job, we have Google Maps recording every journey we make. And yet, ubicomp was less about having a mobile device or about surveillance, it was the forerunner to the Internet of Things, the ambient life, which is there to make things easier so the fridge talks to your online shopping to say that you need more milk. But what if I go vegan? Do I need to inform my fridge first? Must I really run all my important ideas past my fridge? This is not the semiotic relationship psychologist and mathematician J.C.R. Licklider had when he had his vision of man-computer symbiosis.

I was speaking to someone the other day who monitors their partner’s whereabouts. They think it’s useful to see where the partner is at any given time and to check that the partner is where they said they would be. No biggie, just useful. I mentioned it to another person who said that they had heard several people do the same. I wonder why am I so horrified and other people just think it’s practical.

Insidious or practical? I feel we are manipulated into patterns of behaviour which maintain the status quo.

Last week, I woke up and checked my Fitbit to see how I had slept which is slightly worrying now – I never needed anything to tell me how I slept before – and there was a new box in there: Female Health. I clicked on it. It asked me about birth control, when my next period is due, how long it lasts and so on. Intrigued, I entered the requested data. The resulting box said: Your period is due in eight days. Really? I mean, really? It was wrong even though I had tinkered with the settings. So, then it had a countdown: Your period will last four more days, three more days…etc. Wrong again. And, now it is saying: Four days to most fertile days. This is so irritating. It feels like Argos, you know, how the system and the reality of you getting something you’ve ordered never quite match up. I know together me and my Fitbit can build up data patterns. Will they be insightful? Time will tell. The bits which really concern me is that it said it wouldn’t share this information to anyone, okay… but then it added that I couldn’t share this information either. What? I am guessing that it wants me to feel safe and secure. But what if I wanted to share it? What does this mean? Menstrual cycles are still taboo? I can share my steps but not my periods? My husband and I laughed about the idea of a Fitbit flashing up a Super Fertile proceed with caution message when out on date night.

But, it’s not just me and my Fitbit in a symbiotic relationship is it? Someone is collecting and collating all that data. What are they going to do with that information prying into me and my Fitbit’s symbiotic space? It rather feels like someone is going to start advertising in there offering birth control alternatives and sanitary protection improvements. It feels invasive, and yet I signed up to it, me the person who thinks a lot about technology and privacy and data and oversharing. And, even now as I sit here and think about my mixed feelings about my Fitbit, the idea of wearing something on my arm which only tells me the time, and not my heart rate, nor the amount of steps I am doing, feels a bit old-fashioned – I am myself am a victim of the myth of progress. I am user and used. Confession, I regularly lie in bed pretending to be asleep to see if I can fool my Fitbit. It’s changing my behaviour all the time. I never used to lie in bed pretending to be asleep.

Back in 2006, I watched Housewife 49, it was so compelling, I bought the books. Nella Last was a housewife in Barrow-in-Furness who kept a diary along with 450 other people during and after the war. It was part of the Mass Observation project set up by an anthropologist, a poet, and a filmmaker, which sounds rather like the maker culture of HCI today. They didn’t believe the newpapers reporting of the abdication and marriage of King Edward VII, so went about collecting conversation and diary entries and observations on line. Rather like today, we have social media with endless conversation and diary entries and observations. The newspapers are scrambling to keep up and curate other peoples’ tweets because they have traditionally been the only ones who shape our society through propaganda and mass media. Now, we have citizens all over the world speaking out their version. We don’t need to wait for the newspapers.

We are living through a mass observation project of our own, a great enormous social experiment and it is a question worth asking: User or used? Who is leading this? And what is their goal? And, then we have the big companies collecting all our data like Google. And, we all know the deal, we give them our data, they give us free platforms and backups and archives. However, it doesn’t necessarily mean that they are right about the results of their research on our data, or have the right to every last piece of information to use, even if you give it freely, because there is a blurring of public and private information about me and my steps and periods and birth control.

Anthropologist Agustín Fuentes has written a thoughtful article about the misuse of terms such as biology in Google’s manifesto and consequently, the sweeping generalisations to which it comes. Fuentes says we have no way of knowing what happened before we collected data and even now as we collect data, we have to maintain our integrity and interpret it correctly by using terms and definitions accurately. Otherwise, we think that data tells the truth and stereotypes and bias and prejudices are maintained. I love the quote:

If you torture the data enough, it will confess to anything.

Information is power. Hopefully, though, there are enough anthropologists and system designers around who can stop the people who own the technology telling us what to think by saying they are having insights into our lives whilst peddling old ideas. We need to pay attention to truth and transparency before we trust so that we can have more open dialogue in the true sense of the word – an exploration of a field of possibilities – to lead to real and effective change for everyone.

Let us all be users not the used.

[Part 4]

9 comments