It’s telling me what I’ve already done, accurately, and with a better vocabulary.

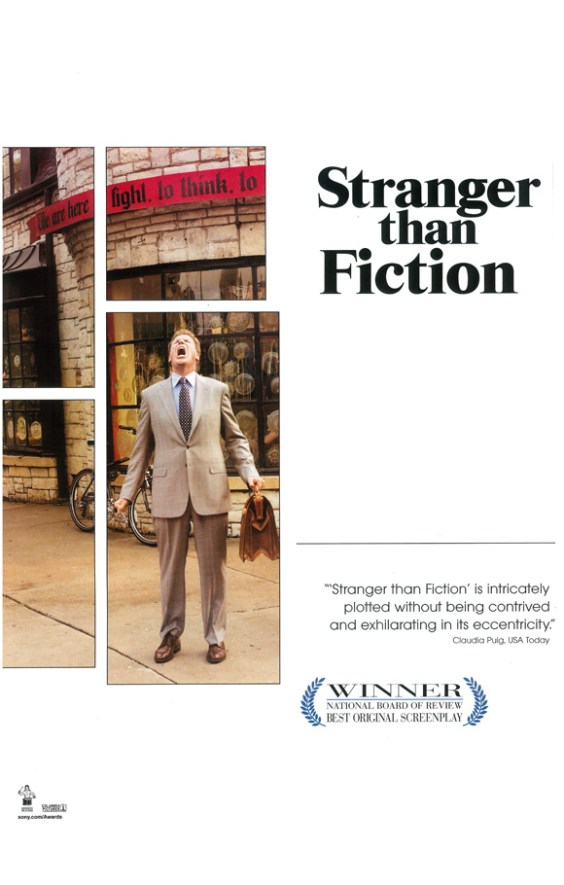

– Harold Crick, Stranger than Fiction (2006)

[ Part 1 of 5: 1) The intimacy of the written word, 2) Structure, 3) Archetypes and aesthetics, 4) Women 5) Possession, the relations between minds]

E M Forster said that he wrote the last two chapters of a Passage to India whilst under the spell of T S Lawrence’s The Seven Pillars of Wisdom, which shows that whilst writing is a solitary process, and reading can be too, both are acts of intimacy, in the true sense of the word.

Intimacy is a lovely word. It means comfort and familiarity which is found in a shared space of connection. It is much bigger than just a euphemism for sex. Intimacy (or connection) gives our lives meaning. We want to be seen and understood. Well told stories, fictitious or otherwise, can do this. They tell us we are not alone, that someone else understands the very experience that has bruised or filled up our hearts, and that someone know how we feel. Stories explore our hopes and fears. They teach and inspire us. And, they describes us, as Harold says above: accurately, and with a better vocabulary.

Sharing is caring

Imagined and real experiences are managed in the same way by the brain which means that stories create genuine emotions and a sense of being in a certain place or space, and we respond accordingly. Consequently, we fall in love with characters (even scary Heathcliff regularly makes it into the top 10 romantic heroes lists), or we feel bereft when a book ends. It has all felt so special, so intimate, we want to continue being there, in that space.

Fan fiction is one way of spending time in a shared space, though it receives a mixed press. Neil Gaiman is a fan fiction writer as is E L James.

For those who are readers rather than writers, then there is literary and film tourism. We have the studio versions like Harry Potter, or travel agents who take fans to the exact film locations for Lord of the Rings, the Sound of Music, or various places where Jane Austen lived in order to gain more understanding of her life and times, so we can feel closer.

The above examples are well known and extremely popular, but there are many books we put down because that connection hasn’t been made, and we don’t feel that we have anything in common with the writer or the space offered. What is it that entices readers into spending time in a fictional world that a writer has created? What are the key ingredients?

Time for new stories?

Joseph Campbell said that archetypal story patterns are hard wired in our psyche, and I used to believe this. Nowadays, I am wondering if is it just that we have just heard the same stories (or patterns) over and over, that they are familiar and so we connect because we like the familiarity and comfort. But is this enough? For, as resonating as the hero’s quest is, it wasn’t designed for women even they make up 50% of the population. That said, James Patterson says that he writes for women because 70% of his readers are female and our favourite hero’s quest story Star Wars now has Rey.

Last week, I attended an agile management for women seminar where one of the presenters said that there are no archetypes for strong women in business which made me wonder if that is because there are not many in stories. The first question to ask is there should be? Should there be strong female archetypes specifically design to fit into a patriarchal norm? Or, is it time to write new stories and rewrite our business structures so we don’t have to adopt any persona/archetype – armour up – in order to fit in? Thankfully, we have lots of talented women working on the heroine’s quest, author of historical fiction Phillipa Gregory is rewriting history from a feminine perspective, and script writer Shonda Rimes is putting dazzlingly authentic dialogue into women’s mouths, on prime time TV, expressing exactly how society views and validates them only in relation to men. I literally cheer and clap all the way through Scandal.

Reflecting us

If a story is to have meaning for us, if a writer wants to connect to a reader, then it has to reflect the problems that the reader has, perhaps reflecting our day to day lives, or pondering the human condition and the philosophical question: Why we are here, which is why I chose Stranger than Fiction (2006), at the top of this blog. It got mixed reviews but it is funny, clever and moving.

Harold Crick lives a lonely life until the day he starts hearing a female narrating his life and foreshadowing his imminent death. He enlists a professor of literature theory who gives Crick a quiz to figure out what his story is:

Has anyone recently left any gifts outside your home? Anything? Gum? Money? A large wooden horse?

Do you find yourself inclined to solve murder mysteries in large, luxurious homes to which you may or may not have been invited? …

Are you the king of anything? King of the lanes at the local bowling alley. King of the trolls?… A clandestine land found underneath your floorboards?

Now, was any part of you, at one time, part of something else? …

This (abridged here) quiz is hilarious, clever and recognisable, because we all do it, even though it can seem naive and silly to refer to literature as a guide, and that message is even enforced in literature: John the so called savage from Brave New World tragically struggles because he uses The Complete Works of Shakespeare as his guide to life.

Affirming life

However, we do it subconsciously or otherwise because like Harold, we sometimes fret about whether we are living in a tragedy or in a comedy, which might cause us to ask how life should be lived and we might feel like we are living the wrong story. In the end, Harold embraces his fate and the business of living, connecting and falling in love – all the lovely things we want in a story, and in life too.

It is the polarities of life and death which create action and tension, and, any story which explores death but embraces life, according to Christopher Vogler author of The Writer’s Journey, makes it one which is emotionally universal and intelligent.

But, that doesn’t answer the question of what makes a great story. Are polarities enough? Do we need a gestalt whole of time and place, plot and character? What about archetypes and blueprints for resonance? And shared emotions for that intimacy we crave? How do we go about designing story?

Let us tell some stories and see.

14 comments