Death and life are in the power of the tongue: and they that love it shall eat the fruit thereof, Proverbs 18:21, KJV.

Recently, in the Guardian, David Lodge was rereading Anthony Trollope’s last novel The Fixed Period. The story takes place on the fictional island of Britannula, where its Assembly wish to make euthanasia compulsory for everybody over the age of 67. After some debate the age is fixed at 67½. The idea is that the oldies can prepare for death, be feted and celebrated, and go out with great dignity amongst all their creature comforts.

Lodge tells us that the novel was badly received because it was so unlike the rest of Trollope’s work but reflected what was on the 66-year-old Trollope’s mind as he wrote it. Lodge quotes from Trollope’s letters to show us that Trollope meant every word: He felt that he would rather die than be old. He did not fear death, rather he feared being incapacitated and helpless.

Both his fear and his wish came true. In November 1882, Trollope suffered a severe stroke and was paralysed and unable to speak, before dying early December 1882, aged 67½.

Trollope, was a master storyteller. His oeuvre, his life, and his death demonstrate the power of fiction and the power of the stories we tell ourselves. We make our world with our stories, for good and for bad because we are human and embodied. That is, we experience the world through our bodies and their limited senses and then our brain interprets the experience in light of our past experiences. We pattern match, so we view a new experience as a similar bad or good one that we have previously experienced, and then we behave in such a way that makes this new experience fit the good or bad ones that went before it. So, we predict the outcome and make that outcome true and add it to our list of experiences. Ultimately, all we have are our thoughts and experiences, and the stories we tell ourselves. And we tell ourselves stories every minute of everyday often whilst not paying attention to the reality of what is really happening.

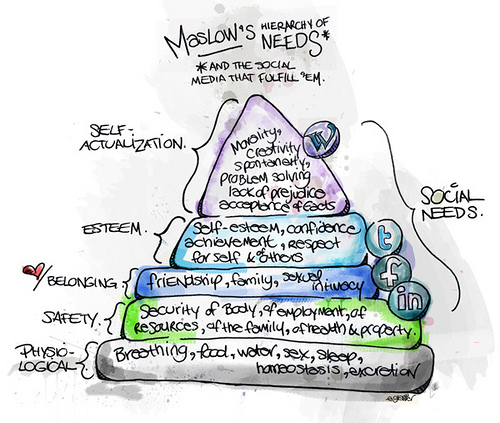

Some people cast themselves as victims in the story of their lives. They dwell on past sadnesses which feed into future interpretations of stories of defeat and further sadness. Life Coach, Martha Beck calls this approach to life story fondling. People get out their sad stories and fondle them and polish them instead of letting go and letting them fade with time. Beck recommends that we reeducate ourselves and choose narrative therapy, an approach where we learn to reframe our stories in different ways.

Some people can do this already and seem to be extremely lucky people who lead charmed lives. Beck believes that we can all learn to cast ourselves as heroes so that we can rewire our brains to interpret future events more positively and to lead our own charmed lives.

Sounds great! But it is extremely difficult to do. Yogis spend their whole lives meditating in order to wipe the lense of perception clean in order to see things as they really are, and not how we think they are. The idea behind seeing reality as it is rather than what story we tell in our heads, is that if we see things as they are, rather than what we think they are, life is generally better. But how is that possible? Terrible things occur everyday in daily life, disasters befall us, atrocities are committed to us, true. But often, we can make a drama many times worse by saying it shouldn’t have happened and then compounding the difficulty of the situation by acting under pressure and creating yet more difficulties. And sometimes small dramas seem as bad as the enormous ones because we live them differently in our heads to the reality of what has happened. As Sophocles put it: The greatest grieves are those we cause ourselves.

Spiritual Teacher Iyanla Vanzant talks about how we terrorise ourselves with our stories often about things that do not happen. We cause ourselves pain. Or, we miss out on life because we are believing a story that simply isn’t true. In Tapping the Power Within Vanzant demonstrates this by telling a story of how she never ate okra. She told everyone that she didn’t eat it, she hated it, until one day her neighbour cooked her some and brought it round and it was so delicious. Vanzant had been missing out on this lovely vegetable her whole life, because she had copied someone else’s I hate okra story and took it as her own. How much more had she missed out on because she believed that the good stuff wasn’t relevant to her? She goes on to say that we need to get ourselves better stories and question the ones we have right now, instead of just taking on other peoples’ stories with their habits and learnt helplessnesses.

Spiritual Teacher Byron Katie says similar things in her book Loving what is, and gives us a process to free ourselves of our terrible stories and learn to tell ourselves new stories based in reality. She says that it is not reality which is the problem, it is our thinking. Like Vanzant, Katie says we terrorise ourselves in our heads, instead of seeing what is, we interpret and attach all sorts of pain to things that might or might not be happening. Each time something causes you pain ask: 1) Is it true? 2) Can I absolutely know it’s true? 3) What happens when I think that thought? 4) Who would I be without that thought?

The results are surprisingly liberating. You can stop the thoughts, stop the stories, and observe without emotion what really is happening. Then, instead of the negative thoughts in the negative stories which can destroy your whole day, your whole life, you can create a space and in it, there is peace. Katie firmly believes if we all question our stories and base ourselves in reality, we can become more peaceful and then in turn the world becomes a peaceful place. As Mahatma Gandhi said, Be the change you want to see in the world.

And that is a great story to tell yourself:

Today, I put on my superhero hotpants and changed the world.

14 comments