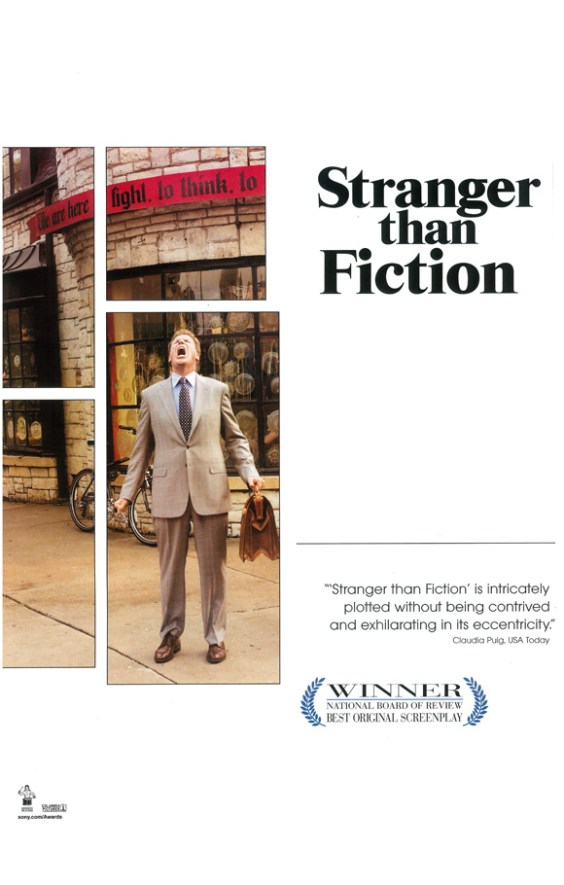

Some plots are moved forward by external events and crises. Others are moved forward by the characters themselves. If I go through that door, the plot continues. The story of me through the door. If I stay here……the plot can’t move forward, the story ends. Also if I stay here, I’m late. – Prof Jules Hilbert, Stranger than Fiction (2006)

[ Part 2 of 5: 1) The intimacy of the written word, 2) Structure, 3) Archetypes and aesthetics, 4) Women 5) Possession, the relations between minds]

In life, stories are the way we communicate, so much so that eyewitness accounts in court which conform to a story pattern are the most likely to be believed as truth.

In these uncertain times, thankfully we are questioning the news shown on TV and in the newspapers, because media companies have long used the old adage first uttered by Mark Twain: Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

But, what is truth? Semiotics, the study of how meaning is created, is the only measure of truth human kind has been able to devise encapsulated in the question: Does it feels right? When the answer is yes, this is because the new data often fits with standard or known truths that we refer to already. It feels true, it is familiar, it adds to our understanding of meaning.

Meaning comes from contrast. The greek god Agon (agony) represents the struggle and wrestling we do in order to create meaning, from light and dark, good and bad, love and hate. We use polarity to organise our thinking.

It works the same way in fiction only in a tidier, yet larger than life, fashion. We have our goodies and baddies. We have our agony and ecstasy. And we, the readers, figure it out because we interpret the polarities and the story structure to derive meaning.

Narrative or story structure

The story of any individual in any narrative can be described in terms of deterioration or improvement, and the choice of which term to use depends on the point of view chosen by the narrator.

Normally we have a protagonist (our goodie) and an antagonist (our baddie) in polarity. As the goodie’s situation improves, the baddie’s will deteriorate. The narrator can invert this relationship and create a tragedy. When we are looking at the baddie as our main protagonist from that point of view, we are sympathetic to their plight, they become our goodie. If they do something morally questionable we go on an exploration with them. Often this a cathartic one. Their story helps us negotiate our own conflicts unconsciously or otherwise. Some of our most sympathetic characters are baddies, like Macbeth, nothing he does is admirable, yet we are there feeling for him until the end.

Sometimes the main protagonist gets improved by something coming in from outside the narrative. If this is near the end of a story then we can feel unsatisfied, because it does not feel true, like the Greek deux ex machina (literally machine of the gods), the equivalent of then we all went home for tea. This rarely happens in life so it doesn’t feel true, unless it happens in comedy like Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim. In that story though it doesn’t really matter how our ‘hero’ gets saved as we know he would be much better off anywhere else than where he is. It is ok. Comedy aside, if we don’t get to live through the full range of emotions, we don’t get closure and we feel dissatisfied with the ending.

Closure is a psychological term first suggested in Gestalt which explains how incomplete shapes are interpreted by the brain as whole. From the 1990s the term has been used with respect to relationships. So, when a relationship is over, sometimes we need closure to find an answer especially if it ended ambiguously, so we can learn from it and manage our world or people next time, or so we like to think.

Managing expectations

This is because according to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs we need certainty. We need to feel certain that our physiological and safety needs are met, this in itself feels like a reward. Consequently, in a story we are rewarded by the plot unfolding in a particular way.

But, we are complicated and only want certainty up to a point. Social media shows us that the information we share most often is surprise. For more than anything once we have a low level of certainty we need to be lifted up and inspired. So, in any given story we want it to follow a specific path (certainty) but have surprise twists in the tale. This enables us to transcend ourselves.

It doesn’t matter what story is being told, it matters if it is being told in the right way. As Mythologist Joseph Campbell once said: We don’t need a why, we just need a how. The medium is the message or form follows function, the actual content is to a certain extent, irrelevant, as long as it hits the main beats and has the right scenes with enough surprises in them to follow the story pattern we are expecting but with a freshness that transcends both the story pattern and our thoughts.

We have models to explain the world around us, ourselves and our behaviour. It is the same when we are being entertained. We construct the pattern and the meaning as we go along so that even if a certain narrative merely infers something off screen/scene, we still know how to automatically assimilate it into the rest of the narrative to make it into the complete story. So, when something inexplicable happens either in fiction or in real life, it leaves us baffled and without a way of incorporating it into our explanations.

Ups and downs

The general pattern of life is that we work up to something, we have a beginning, a middle, a climax and an end. The momentum gets going, we have highs and lows – those moments of great joy and those moments when we think we can’t stand it a minute longer, in all of our activities from sex and childbirth to prolonged hospital treatment, shopping in IKEA, and even meditation. Our emotions follow this pattern too. Think of laughter, of crying, or a wave of grief. It is the same so it seems logical that our stories would follow a similar pattern.

Thriller editor Shawn Coyne in his book Story Grid refers to Kubler-Ross and the five stages of grief as a useful tool to model change, as all stories are about change and says: Even those wonderful literary novels in which nothing happens… the characters’ moods and ideas are constantly changing.

Patterns and genres

Depending on our reading tastes, we know the stories, we know which pattern to follow and it doesn’t matter where it sits on the often debated scale of entertainment: genre or literary, all action or internal, we feel when something is emotionally true because it is meaningful to us.

Here are some random patterns to think about:

- Hero’s quest: The hero receives a call to action, goes on an adventure, has trials and tribulations, allies and foes, nearly falls at the end, returns home to great reward.

- Chick lit: The girl has problem in life, there is a cute guy, the problem becomes much bigger, everything looks bleak, she pulls it together as she is smart, solves her problem and gets the guy.

- Thriller: Personal stakes life/ family/career are high enough to make the reader sweaty, often internationally the protagonist is chased about, has a show down with the antagonist, and wins.

- Murder mystery: There is a closed setting, a murder weapon, a body, detectives, we then find out the motive, the villain, and tie it up. We can even model it in a computer (model-based machine learning).

- Bildungsroman: A sensitive soul suffers a loss or tragedy, journeys to fill that vacuum with experiences, gains maturity gradually, struggles then accepts values of society.

- Love story: Two people meet, hit it off, something gets in their way, they are separated, and get back together at the end. Or don’t (tragedy).

There are many others: rags to riches, revenge, forbidden love, unrequited love, sacrifice, rivalry, disaster, recovery from grief, transformation, and so on.

Sometimes these patterns are combined into bigger patterns and in a different world created on another planet or fantasy land, or supernatural events occur. However, even if the landscape and events seems totally alien or paranormal, the emotions and behaviour of the characters are always human, always meaningful, and can always resonate.

If they don’t, we stop reading.

Formula or familiarity

It may seem formulaic but Christopher Vogler says in his book The Writer’s Journey: Unconventional art does not intersect with commonly held patterns of experience.

Rather like design, a certain amount of form is necessary to reach a wider audience who will expect to enjoy it so long as it has something fresh going on within the constraints of the formula. Vogler says that film studios use story design principles to evaluate scripts because they do so many, and the stories which capture us as an audience, capture our shared experiences:

We are all looking for ourselves in a dark wood, in the mirror of others, in the stories of life...

Which is why when we pick up a book or watch a film, we want to connect to a story which has meaning for us or at least for the characters in it, and that meaning is found in structure.

5 comments